JC: There’s a sweep to your new book, many

forms, many subjects – San Francisco, sex, Viet Nam, alienation of the self by

digital means, larger political history from the 60s to the present, poets and

heroes of pop culture, domestic bliss and its opposite – I could go on. To me,

it has, for lack of a better term, ‘a novelistic breadth’.

K: I’m a

frustrated playwright, essayist, short story writer, pundit, Casanova, cultural

anthropologist...the list goes on. Which leads to a crazy quilt of approaches

and subject matter: it all gets poured into poems. There are no conscious

themes, just inclinations, preoccupations, obsessions. It’s like being

attracted to a certain “type” of woman. I’m pretty promiscuous when it comes to

poems. The flip side is also true, of course. What type of woman – or poem – is

attracted to me? The woman, or the poem, usually has the final say.

JC: Can you speak a little about the early stages

of this project? Did it organize itself early in your mind into this large,

capacious collection or did that form appear later to you, organically, as the

poems were assembled, added to and edited?

K: I don’t have an easy time putting a

manuscript together, precisely because my poems are so different from each

other. The first draft of this book was twice as long as it turned out to be. I

tend to throw in the kitchen sink then pit poems against each other, gladiator

style to fight it out amongst themselves. Then I show what’s left to a few

trusted people – including you, as you’ll recall, perhaps not a happy memory –

and try to get other people to make the hard decisions for me. When that fails,

I have drawn-out arguments with myself. This all takes years and years.

JC: Seldom does one encounter a book of poetry

that works so many different forms. Poets, one would be inclined to believe,

prefer their books to exemplify a singular formal aspect. What are your

thoughts about form, the formal nature your poems assume?

K: I never consciously think of “form,” per

se. I go with Creeley on form being an extension of content, and try to listen

to poems, hoping they will tell me what they should look and sound like, what

clothes look good on them, whether their socks match. At times I feel like

those homicide detectives on tv who talk to corpses, asking “Who did this to

you? And why?”

JC: Was there any poem which began in one

form, only to end up in a form radically different than initially intended?

K: More than one, including “The Eternal

Present,” which closes the book. It started out as a prose poem, then had lines

breaks, then stanza breaks for extra breathing room. Brilliant fix or arbitrary

reformatting? Not for me to say.

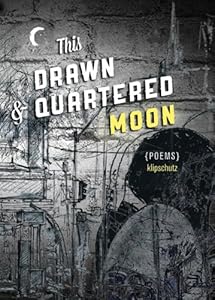

JC: Satire appears throughout “This Drawn

& Quartered Moon.” Many times I found myself reading a poem and suddenly I

was laughing. Lines leapt out at me because they seemed hilarious, even as the

subject was serious. But Beckett, Larkin, Berryman could all be very funny,

even Plath had her darkly humorous moments. More recently Minnis, Leidner, and

Feng Sun Chen all use satire and humor in their poems. What is your approach to

humor in your poems? How does one know when it is appropriate, when it isn’t?

K: I have been accused of being “too clever by

half,” and I’m on the lookout for that tendency, especially on rewrite. There’s

a lot we can all learn from Beckett about paring back. And you’re right about

Plath’s odd humor. Good point, rarely mentioned. The comedic, I guess, works to

deflate pomposity, or to break the ice, maybe even get the reader on your side,

if you go in for that sort of thing. And it can set up a sudden burst into

different weather entirely.

JC: One of my personal favorites, humor-wise,

is “The New Library” where “ … Chief Librarian Bleep plays cards, / then

photoshops Gutenberg’s head /onto a football sailing over a goalpost.”

K: Well, thanks. That one’s based on a long

essay in The New Yorker from the 90s by Nicholson Baker, about the rebuilt San

Francisco Main Library, and the destruction of the card catalogue system, which

was championed by Chief Librarian Ken Dowlin, an ex-Marine, who wanted to turn

the whole library digital. Nicholson Baker, by the way, hates contemporary

poetry, as evidenced by his novel The Anthologist – which is more than strange,

given his own experiments with form in fiction. I handed him a version of the

poem when he read at that very library.

JC: There are also moments of delicate,

heartfelt love. “With Colette at the Edinburgh Castle” strikes me as one such poem.

It is delightful all the way through, but the ending seems special to me, a

public kiss a declaration and a rite, and the sense of homecoming for the poet.

Great Britain is home for poetry in the English language. American poetry could

not exist without English poetry. Tell me about this poem.

K: I hear British English every day, lucky me,

from my wife Colette. The English can use language as a weapon, and at times

I’m on the receiving end, which is less than fun. As to the poem, Colette has

mixed feelings about it. She thinks it portrays her as liking the occasional

drink. Which if you knew her...never mind. My friend John Lane gets the credit

for the way the poem concludes. It used to end “...hearts in Highlands, faintly

bitter halfway home.” John told me, basically, “You write so few love poems,

don’t screw this one up on the one yard line.” If it wasn’t for him, I would

have screwed it up on the one yard line.

JC: Striking poems abound in this book,

including two of the ghazals, and the prose poem “Oliver Othello King, Jr.”

What was it about the ghazal that appealed to you? And is there a context the

reader doesn’t get to see in the prose poem? It’s a powerful statement, and

seems to arrive out of poetic reportage rather than a purely poetic impulse.

K: There were eight ghazals in my previous

book. The few this time around exhausts my output. It’s an exacting form,

imported from other languages and cultures. Jim Harrison did a series that

stand up, for me anyway. How I see the form is akin to a Wallace Stevens

sensibility, theme without plot, and I’m always happy when I can channel

Stevens. Some of his poems make little surface sense, but keep drawing me back.

The problem with channeling Stevens is that if you hit the wrong button you

might tune into John Ashbery instead. At which point, god help you.

Oliver Othello

King, Jr. was a Viet Nam vet I met on public transportation. The poem was a

gift from him, completely: his experiences, his voice. All I did was write it

down. Then rewrite it for about fifteen years, trying to get out of his way.

You’re right as rain, it’s reportage, capturing about fifteen minutes of

experience, trying to bottle what felt to me like magic.

JC: Roughly midway through your book is the

poem “Elvis the First,” which seems central to me, not only physically but

thematically, historically: it reaches back to the earlier poems and prepares

the way for those that follow. What is it about this poem, apart from

chronology, which makes it such an important one, both for you personally and

for the entire book?

K: The poem is “about” Elvis Presley, but also

about my family, and reaches back to some rough times, when the ’60s were just

kicking into high gear, when my siblings and I were starting to do drugs, and

my parents didn’t have a clue how to handle us. Then my dad became Elvis’s

doctor. Maybe if Elvis had come over for dinner, as I fantasize in the poem, he

could have helped. After all, he did have that drug enforcement badge Nixon

gave him! Seriously, the poem gave me a way to write about family, and as

someone else pointed out, it encompasses four different forms in one poem,

hopefully unifying them thematically.

JC: Your poetic practice is complemented by

your songwriting. What do you consider the essential differences between

writing poems and writing songs? How does the song-practice influence your

poetry?

K: I’ve been writing songs since the

mid-1980s, and with Chuck Prophet, on and off, since about 1990. I’ve been

lucky to have collaborators who insist that a song be a song, rather than some

hybrid between poetry and music. Poetry has to carry its own music, and a song

has a melody, which is more important than the words. The words only matter at

all if the melody is memorable, or at least enticing. And songs benefit from

repetition, hooks. “Don’t bore us, get to the chorus.” Songwriting is usually

concise. Maybe it helps keep my poems from “going on,” as the English say.

JC: Such a large collection as “This Drawn

& Quartered Moon” suggests many precedents, many traditions. From your

perspective, what are the major influences that helped you when writing this

book?

K: So many influences, so much thievery. I

only wish I had incorporated, like those guys in D.C., Thievery Corporation. A

DJ duo who also own a string of high end restaurants. What a life! And we had

to be poets instead. My influences are all the usual suspects, from Homer to

Dylan, with a lot of painters and comedians and architects and baristas thrown

into the mix. Practically everybody except Whitey Bulger. Truthfully, your

whole life up to that point goes into every poem, every draft of every poem.

And my poems have to endure about fifty drafts, on the average, at my hands.

The hard part is erasing the stitches so hopefully the reader feels like the

poem just kind of happened, poured out in one sitting.

JC: The book starts with a prologue of sorts,

a “Memo To Wordsworth,” and proceeds to a survey of urban particularities, “In

Memory of Myself.” And concludes with “The Eternal Present.” Where is this

special present, is it urban, is it contemporary? Is it found in poetry, the

pursuit of poetry, quietly and diligently? Does it encompass both personal and

private, the political, the historical? Is this, ultimately, the gift that

poetry has to offer all of us – the few of us – who are alert to its

persuasions: namely, the eternal present?

K: Eliot, I think, said all cultures exist

contemporaneously, and that the present reconfigures the past, changes the way

we look at it. Which, to me, is the promise of poetry, getting across,

communicating, tying things together that felt unrelated before the poem

unifies them. For me, as a reader, the right poem at the right time can

re-enchant the world, make me see it through new eyes. Everything is

interwoven. And, as Dylan observes, broken. Poetry can’t put Humpty Dumpty back

together again, but maybe it can make something of beauty from the pieces.

JC: One final thing: Is Frank O’Hara invoked

in the opening lines of “The Eternal Present”? “8:46 a.m. 62 degrees./The

parking lots are full, the message was delivered...”?

K: Now that you mention it. I’m always on the

lookout for an opportunity to lift an O’Hara riff. His precision as to

coordinates. Why should we care what street he is walking down, and when, what

book he is carrying, and who he is going to visit? But we do!

-END-

klipschutz (pen name of Kurt Lipschutz) is a native

Californian. He is the author of several previous collections, including Twilight

of the Male Ego and The Erection of Scaffolding for the Re-Painting of

Heaven by the Lowest Bidder. His work has appeared in periodicals in the

U.S., Canada, and the United Kingdom, and numerous anthologies, including The

Outlaw Bible of American Poetry. Also a songwriter, he co-wrote Chuck

Prophet’s 2112 disc, the critically acclaimed Temple Beautiful.

Jon Cone grew up in Richmond Hill, Ontario, and has lived for the past twenty years in Iowa

City. For nine years he edited

the international literary review World

Letter (1990-1999); currently he is a poetry editor for the online journal Atlas & Alice. His published books

include Least (2012), The Plesyre Barge (2010), Family Portrait with Two Dogs Bleeding (2009), and Sitting Getting Up Sitting Again (2006). He has published widely, holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Vermont College, and works

as an adjunct faculty member for Rasmussen College.